6. 1930-40s-WWII: Images and Emotions, Citizens as Consumers

more images below

more images below

“Anyone whose job it is to select war posters can be sure of getting only the most effective posters by asking two simple questions:

Does the poster appeal to emotions?

Is the poster a literal picture in photographic detail?

THE MOST EFFECTIVE war posters appeal to emotions. ...unless a war poster appeals to basic human emotions in both picture and text, it is not likely to make a deep impression.

The poster should be a picture, not an all-type poster or symbolic design. And by a picture is meant a true and literal representation, in photographic detail of people and objects as they are, and as they look for millions of average people who make up the bulk of the population of the United States.”

— Recommendations based on a survey of war posters conducted by Young & Rubicam, Inc., between March 16 and April 1, 1942. 20

Oh boy, but there's an ocean

Of joy in promotion,

Answering the question

“What's in it for me?”

Settling the digestion

Of the Land of the Free!

That's the stuff to feed the Rubes,

Subway Chumps and City Boobs!

Aren't you on to the surprising

Way they fall for Advertising?...

Try this delicious health-building War!

Buy all you need—then buy some more!

Never mind what we're fighting for!

Customers, customers, come and buy!

A short girdle does not bind the thigh.

We're the Salesmen of the OWI...

Read full poem...

— Poem by William Rose Benét, friend of the unhappy OWI writers, published in the Saturday Review, May 8, 1943.

By 1941, newspapers, newsreels and magazines — especially LIFE — regularly exposed the American public to photographic images and a new visual language for conveying information about current events. From these sources, citizens learned to equate documentary photography with truth. 21

“World War II came at a favorable time for building unity by visual means.”

— Historian George Roeder, The Censored War: American Visual Experience During World War Two.The strategies of persuasion developed for marketing goods influenced the style and design of war posters produced in the 1940s. By this time, advertisers used images to appeal to emotions rather than text to appeal to reason. Posters shifted away from using the “reason-why” style of persuasive communication used during WWI.

The advertising industry, which had been under attack in the 1930s for manipulating consumers and promoting unchecked consumerism, formed the Advertising Council in June of 1942. They volunteered ad space and time to assist the Office of War Information with government wartime propaganda, and to help improve their own industry's public image.

Comparisons of posters from both wars suggest how the Council, composed of corporate advertisers and advertising agencies, became a “private vehicle for public information and persuasion.” 22

“Business desires to create an attitude about the facts, not communicate them. And only about some of the facts… to say as little as necessary in the most impressive way.”

— Art director William Golden, commenting on his profession. 23The tremendous volume of goods required to wage a war in Pacific and European theaters meant shortages at home and skyrocketing prices for homefront Americans. By 1942, many government officials believed the voluntary rationing strategy of WWI would be insufficient to offset the larger operation and greater needs of WWII.

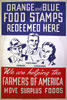

The Office of Price Administration (OPA), whose job was to look after civilian needs, argued for food planning, including a program of economical and equitable distribution. To protect homefront consumers, they concluded, food needed to be rationed.

“It is obviously fair that where there is not enough of any essential commodity to meet all civilian demands, those who can afford to pay more for the commodity should not be privileged over those who cannot. ...where any important article becomes scarce, rationing is the democratic, equitable solution.”

— President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Cost of Living” message to Congress, April 27, 1942.Predicting that Americans would dislike the authoritarian nature of mandatory rationing, administrators carefully emphasized the democratic, equitable nature of this method of conservation. They enacted a point system designed to limit consumption of certain products, while still affording individual households control over their food choices.

Among the 30 million consumers OPA affected on a daily basis, many recognized the benefits of price controls and OPA enjoyed popular support. To many business owners, however, government price controls signaled a growing regulatory state. OPA, as a popular government agency, challenged the right of private industries to set their own prices and sell their items freely. 24

The Ad Council's posters appeared to serve two goals 1) supporting the Office of War Information's need to inform the citizenry, and 2) furthering the admen's vested interest in free enterprise and businesses that might hire advertising agencies after the war. Some posters show a desire to convey messages that were simultaneously supportive of the war and friendly to private businesses.

Many government employees of the OWI believed their most urgent task was to inform Americans as much as possible about the war. A few who worked alongside members of the Ad Council claimed the admen discouraged honest information and honest depictions of war. Internal conflicts based on rival ideologies led to the 1943 resignation of many OWI writers and the Graphics Bureau chief, Francis Brennan.

In his resignation letter, Brennan agreed that some advertising techniques, like printing and distribution, were valuable, but the “psychological approaches” the admen had developed in the 1930s seemed at odds with his role as a public servant charged with disseminating information about war:

“In my opinion those techniques have done more toward dimming perceptions, suspending critical values, and spreading the sticky syrup of complacency over the people more than any other factor in the complex pattern of our supercharged lives.” 25

Posters in this section (and in the next one) reflect overlapping priorities of government, advertising and commerce. Many of the materials carried public messages and were designed specifically for shoppers in retail environments or for businesses catering to consumers.

Image Gallery |

Next Section